സ്ത്രീ ലിംഗഛേദനം

ഉഗാണ്ടയിലെ കാപ്ചോർവയ്ക്കടുത്തുള്ള സൈൻ ബോർഡ് | |

| വിവരണം | വൈദ്യശാസ്ത്രപരമായ കാരണങ്ങളാലല്ലാതെ സ്ത്രീകളുടെ ബാഹ്യ ലൈംഗികാവയവങ്ങൾ പൂർണ്ണമായോ ഭാഗികമായോ നീക്കം ചെയ്യുന്ന എല്ലാത്തരം പ്രക്രിയകളും. ലൈംഗികാവയങ്ങൾക്കേൽപ്പിക്കുന്ന പരിക്കുകളും ഇതിലുൾപ്പെടും.[1] |

|---|---|

| മറ്റുള്ള പേരുകൾ | ഫീമേൽ ജെനിറ്റൽ മ്യൂട്ടിലേഷൻ, ഫീമേൽ ജെനിറ്റൽ കട്ടിംഗ്[2] |

| പ്രയോഗിക്കപ്പെടുന്ന സ്ഥലങ്ങൾ | പടിഞ്ഞാറൻ ആഫ്രിക്ക, കിഴക്കൻ ആഫ്രിക്ക, വടക്കൻ ആഫ്രിക്ക സബ്-സഹാറൻ ആഫ്രിക്ക; മദ്ധ്യപൂർവ്വേഷ്യ ഉൾപ്പെടെ ഏഷ്യയുടെ ഭാഗങ്ങൾ.[3] |

| ഇരയായ സ്ത്രീകൾ | 2013-ൽ ലോകമാസകലം 14 കോടി സ്ത്രീകൾ. ആഫ്രിക്കയിൽ 10.1 കോടി[1] |

| ചെയ്യുമ്പോൾ സ്ത്രീയുടെ പ്രായം | ജനിച്ച് ഏതാനും ദിവസങ്ങൾ കഴിയുമ്പോൾ മുതൽ 15 വയസ്സുവരെ; ചിലപ്പോൾ പ്രായപൂർത്തിയെത്തിക്കഴിഞ്ഞും ഇത് ചെയ്യാറുണ്ട്.[4] |

സ്ത്രീ ജനനേന്ദ്രിയം മുറിക്കൽ, സ്ത്രീ പരിച്ഛേദനം എന്നും അറിയപ്പെടുന്ന സ്ത്രീ ജനനേന്ദ്രിയ ഛേദനത്തെ (FGM), “വൈദ്യശാസ്ത്രം നിഷ്ക്കർഷിക്കാത്ത കാരണങ്ങളാൽ, സ്ത്രീയുടെ ബാഹ്യ ജനനേന്ദ്രിയം ഭാഗികമായോ പൂർണ്ണമായോ നീക്കംചെയ്യലോ സ്ത്രീയുടെ ജനനേന്ദ്രിയ അവയവങ്ങൾക്ക് വരുന്ന മറ്റെന്തെങ്കിലും മുറിവോ ഉൾപ്പെടുന്ന എല്ലാ നടപടിക്രമങ്ങളും” എന്നാണ് ലോകാരോഗ്യ സംഘടന (WHO) നിർവചിക്കുന്നത്.[1] ഉപ-സഹാറനിലും വടക്കുകിഴക്ക് ആഫ്രിക്കയിലും ഉള്ള 27 രാജ്യങ്ങളിലെ ഗോത്ര സമൂഹങ്ങളും ഏഷ്യയിലെ ചില വിഭാഗങ്ങളും മറ്റിടങ്ങളിലുള്ള കുടിയേറ്റ സമൂഹങ്ങളും ഒരു സാംസ്കാരിക ചടങ്ങായി FGM പിന്തുടർന്നുവരുന്നു.[5] ഛേദനം നടത്തപ്പെടുന്ന പ്രായം പലയിടത്തും പലതാണ്. എന്നിരുന്നാലും, ജനനം മുതൽ പ്രായപൂർത്തിയാകുന്നത് വരെയുള്ള സമയത്താണിത് നടക്കുന്നത്. ദേശീയ കണക്ക് ലഭ്യമായ പകുതി രാജ്യങ്ങളിൽ, അഞ്ച് വയസ്സ് പ്രായമാകുന്നതിന് മുമ്പുതന്നെ ഛേദനം നടത്തപ്പെടുന്നു. [6]

ഈ സമ്പ്രദായത്തിൽ ഒന്നോ നിരവധിയോ നടപടിക്രമങ്ങൾ ഉണ്ടാകും. ഗോത്ര സമൂഹമനുസരിച്ച് നടപടിക്രമങ്ങൾ വ്യത്യാസപ്പെടും. പൂർണ്ണ ഭഗശിശ്നവും അല്ലെങ്കിൽ ഭാഗിക ഭഗശിശ്നവും ഭഗശിശ്നത്തിന്റെ മുകളിലേക്ക് നിൽക്കുന്ന ഭാഗവും, പൂർണ്ണ ഭഗശിശ്നവും അല്ലെങ്കിൽ ഭാഗിക ഭഗശിശ്നവും യോനിയുടെ, ചുണ്ടിന്റെ ആകൃതിയിലുള്ള മടക്കുകളുടെ ഉൾഭാഗവും നീക്കംചെയ്യുന്നത് ഈ നടപടിക്രമങ്ങളിൽ ഉൾപ്പെടുന്നു; ഈ സമ്പ്രദായത്തിന്റെ ഏറ്റവും ക്രൂരമായ രീതിയിൽ (ഇൻഫിബുലേഷൻ) യോനിയുടെ ചുണ്ടിന്റെ ആകൃതിയിലുള്ള മടക്കുകളുടെ ഉൾഭാഗവും പുറംഭാഗവും യോനിയുടെ പൊതിഞ്ഞ് സൂക്ഷിക്കുന്ന മാംസവും വരെ നീക്കംചെയ്യുന്നു. ടൈപ്പ് III FGM എന്ന് WHO വിളിക്കുന്ന ഈ അവസാനത്തെ രീതിയിൽ, മൂത്രവും ആർത്തവരക്തവും പുറത്തുപോകുന്നതിന് ഒരു സുഷിരം മാത്രമാണ് വിടുന്നത്, ലൈംഗികബന്ധത്തിനും പ്രസവത്തിനുമായി യോനി തുറക്കപ്പെടുന്നു.[7] നടപടിക്രമത്തെ അടിസ്ഥാനമാക്കിയാണ് ആരോഗ്യ പ്രശ്നങ്ങൾ ഉണ്ടാവുന്നത്, എന്നാൽ ആരോഗ്യ പ്രശ്നങ്ങളിൽ തുടർച്ചയായ അണുബാധകൾ, സ്ഥിരമായ വേദന, മുഴകൾ, ഗർഭം ധരിക്കാനുള്ള ശേഷിയില്ലായ്മ, പ്രസവ സമയത്തെ സങ്കീർണ്ണതകൾ, മാരകമായ രക്തസ്രാവം, ലൈംഗിക വേഴ്ചയിൽ വേദന, രതിമൂർച്ഛാരാഹിത്യം എന്നിവ ഉൾപ്പെടുന്നു.[8]

ലിംഗ അസമത്വം, സ്ത്രീകളുടെ ലൈംഗികത നിയന്ത്രിക്കുന്നതിനുള്ള ശ്രമങ്ങൾ, ശുദ്ധതയെയും പാതിവ്രത്യത്തെയും രൂപഭാവത്തെയും കുറിച്ചുള്ള ആശയങ്ങൾ എന്നിവയിൽ നിന്നാണ് ഈ സമ്പ്രദായം ഊർജ്ജം വലിക്കുന്നത്. സ്ത്രീകളാണ് പൊതുവെ ഈ നടപടിക്രമം നിർവഹിക്കുന്നത്. ഇതൊരു അഭിമാനത്തിന്റെ ഉറവിടമായാണ് ഈ സ്ത്രീകൾ കരുതുന്നത്. ഇങ്ങനെ ചെയ്തില്ലെങ്കിൽ തങ്ങളുടെ മക്കളോ പേരക്കുട്ടികളോ സാമൂഹിക പുറന്തള്ളലിന് വിധേയമാക്കപ്പെടുമെന്ന് ഇവർ ഭയക്കുന്നു.[9] ഈ നടപടിക്രമം കേന്ദ്രീകരിച്ചിരിക്കുന്ന 29 രാജ്യങ്ങളിലായി, 130 മില്യണിലധികം സ്ത്രീകളും പെൺകുട്ടികളും FGM-ന് വിധേയമാക്കപ്പെട്ടിട്ടുണ്ട്.[10] പ്രധാനമായും ജിബൂട്ടി, എറിത്രിയ, സൊമാലിയ, സുഡാൻ എന്നിവിടങ്ങളിൽ കണ്ടുവരുന്ന ഒരു സമ്പ്രദായമായ പൂർണ്ണ പരിഛേദനത്തിന് (ഇൻഫിബുലേഷൻ) എട്ട് മില്യണിലധികം പേർ വിധേയമായിട്ടുണ്ട്.[11]

FGM നടക്കുന്ന മിക്ക രാജ്യങ്ങളിലും നിയമം കൊണ്ട് ഈ സമ്പ്രദായം തടയുകയോ നിയന്ത്രിക്കുകയോ ചെയ്തിട്ടുണ്ടെങ്കിലും, നിയമം പലപ്പോഴും നടപ്പാക്കപ്പെടുന്നില്ല.[12] ഈ സമ്പ്രദായം ഉപേക്ഷിക്കുന്നതിന് ആളുകളെ പ്രേരിപ്പിക്കുന്നതിന്, 1970-കൾ തൊട്ട് അന്താരാഷ്ട്ര പ്രയത്നങ്ങൾ നടന്നുവരുന്നുണ്ട്. 2012-ൽ ഈ സമ്പ്രദായത്തെ മനുഷ്യാവകാശ ലംഘനമായി യുണൈറ്റഡ് നേഷൻസ് ജനറൽ അസംബ്ലി പ്രഖ്യാപിക്കുകയും ചെയ്തിട്ടുണ്ട്.[13] ഈ എതിർപ്പിനും വിമർശകരുണ്ട്. ചില വിമർശകരാകട്ടെ നരവംശശാസ്ത്രജ്ഞന്മാരാണ് (ആന്ത്രോപ്പോളജിസ്റ്റ്). സാംസ്കാരിക ആപേക്ഷികതാസിദ്ധാന്തത്തെയും സഹിഷ്ണുതയെയും മനുഷ്യാവകാശങ്ങളുടെ സാർവലൗകികതയെയും കുറിച്ചുള്ള സങ്കീർണ്ണമായ ചോദ്യങ്ങൾ ഉയർത്തിക്കൊണ്ട്, നരവംശശാസ്ത്രത്തിന്റെ പ്രധാനപ്പെട്ട ധാർമ്മികതാ വിഷയമായി FGM മാറിക്കഴിഞ്ഞിട്ടുണ്ടെന്ന് എറിക് സിൽവർമാൻ എഴുതുന്നു.[14]

വർഗ്ഗീകരണം

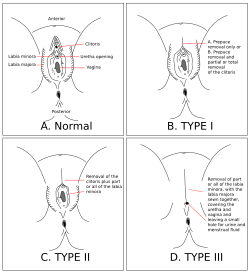

[തിരുത്തുക]ലോകാരോഗ്യസംഘടന സ്ത്രീകളിലെ ചേലാകർമ്മത്തെ നാലായി വർഗ്ഗീകരിച്ചിട്ടുണ്ട്.[15]

- ടൈപ്പ് I സാധാരണഗതിയിൽ കൃസരിയും (ക്ലൈറ്റോറിഡക്റ്റമി) കൃസരിയുടെ ആവരണവും നീക്കം ചെയ്യുന്ന പ്രക്രീയയാണ്.[16]

- ടൈപ്പ് II-ൽ (എക്സിഷൻ) കൃസരിയും ഇന്നർ ലേബിയയും നീക്കം ചെയ്യുന്ന പ്രക്രീയയാണ്.[17]

- ടൈപ്പ് III (ഇൻഫിബുലേഷൻ) എന്ന പ്രക്രീയയിൽ ഇന്നർ ലേബിയയുടെയും ഔട്ടർ ലേബിയയുടെയും പ്രധാനഭാഗങ്ങളും കൃസരിയും നീക്കം ചെയ്യപ്പെടും. ഇതിനു ശേഷം മൂത്രവിസർജ്ജനത്തിനും ആർത്തവ രക്തം പുറത്തുപോകുന്നതിനുമായി ഒരു ചെറിയ ദ്വാരം മാത്രം ബാക്കി നിർത്തി മുറിവ് മൂടിക്കളയും. ലൈംഗികബന്ധത്തിനിടെയും പ്രസവത്തിനും മുറിവ് വീണ്ടും തുറക്കും.[7]

- ടൈപ്പ് IV പ്രതീകാത്മകമായി കൃസരി, ലേബിയ എന്നിവിടങ്ങൾ തുളയ്ക്കുകയോ കൃസരി കരിച്ചുകളയുകയോ യോനിയിൽ മുറിവുണ്ടാക്കി വലിപ്പം വർദ്ധിപ്പിക്കുകയോ ചെയ്യുന്ന പ്രക്രീയയോ(ഗിഷിരി കട്ടിംഗ്) ആണ്.[18]

ചേലാകർമ്മത്തിനിരയാകുന്ന 85 ശതമാനം സ്ത്രീകളിലും ടൈപ്പ് I, ടൈപ്പ് II എന്നീ രീതികളാണ് നടപ്പിലാക്കപ്പെടുന്നത്. ടൈപ്പ് III ജിബൂട്ടി, സൊമാലിയ, സുഡാൻ, എറിത്രിയയുടെ ഭാഗങ്ങൾ, മാലി എന്നിവിടങ്ങളിലാണ് ചെയ്യുന്നത്.[19]

ആരോഗ്യ പ്രശ്നങ്ങൾ

[തിരുത്തുക]ചേലാകർമ്മം ചെയ്യുന്നതിലൂടെ പല ആരോഗ്യപ്രശ്നങ്ങളുമുണ്ടാകുന്നുണ്ട്. ആവർത്തിച്ചുണ്ടാകുന്ന വിസർജ്ജ്യവ്യവസ്ഥയിലെ രോഗാണുബാധ (മൂത്രത്തിലെ പഴുപ്പ്), യോനിയിലെ രോഗാണുബാധ, സ്ഥിരമായുണ്ടാകുന്ന വേദന, കുട്ടികളുണ്ടാകാതിരിക്കുക, മരണകാരണമായേക്കാവുന്ന രക്തസ്രാവം, എപിഡെർമോയ്ഡ് സിസ്റ്റ് എന്ന മുഴ, പ്രസവസമയത്തുണ്ടാകുന്ന ബുദ്ധിമുട്ടുകൾ എന്നിവയുണ്ടാകാറുണ്ട്.[8] കൂടാതെ ലൈംഗികമായി ബന്ധപ്പെടുമ്പോൾ വേദന, ലൈംഗിക സംതൃപ്തിക്കുറവ്, രതിമൂർച്ഛയില്ലായ്മ എന്നിവയും കാണപ്പെടാറുണ്ട്. ആരോഗ്യപ്രശ്നങ്ങൾ, അവകാശധ്വംശനം, സമ്മതമില്ലാതെ ചെയ്യുന്ന രീതി എന്നിവയൊക്കെ എതിർപ്പിന് കാരണകാകുന്നുണ്ട്. 2012-ൽ ഐക്യരാഷ്ട്രസംഘടനയുടെ പൊതുസഭ ഈ പ്രക്രീയ നിരോധിക്കുന്ന പ്രമേയം ഐകകണ്ഠ്യേന പാസാക്കുകയുണ്ടായി.[20]

സിൽവിയ ടമേൽ എന്ന ഉഗാണ്ടൻ നിയമ വിദഗ്ദ്ധയുടെ അഭിപ്രായത്തിൽ ആഫ്രിക്കയിൽ ധാരാളം പേർ ഈ ആചാരത്തിനെതിരായി പ്രവർത്തിക്കുന്നുണ്ട്. ഇതിനെതിരായ ഗവേഷണഫലങ്ങളും നിലവിലുണ്ട്. ആഫ്രിക്കയിലെ സ്ത്രീ വിമോചന പ്രവർത്തകർ ആഫ്രിക്കൻ സ്ത്രീകളെ ശിശുക്കളായി കാണുന്ന "സാമ്രാജ്യത്വ പ്രവർത്തനത്തെയും" സ്ത്രീകളിലെ ചേലാകർമ്മം ആധുനികതയെ വർജ്ജിക്കുകയാണെന്ന ലഘൂകരണത്തെയും എതിർക്കുന്നുണ്ടെന്ന് ടമേൽ അഭിപ്രായപ്പെടുന്നു. ഈ പ്രക്രീയ തുടരുന്നതിന് സാംസ്കാരികവും രാഷ്ട്രീയവുമായ കാരണങ്ങളുണ്ടെന്ന് ടമേൽ വിവരിക്കുന്നുണ്ട്. ഇതിനെ എതിർക്കുന്നത് സങ്കീർണ്ണമാക്കുന്നത് ഇത്തരം കാരണങ്ങളാണ്.[21]

ഇതും കാണുക

[തിരുത്തുക]കുറിപ്പുകൾ

[തിരുത്തുക]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Classification of female genital mutilation" Archived 2013-10-25 at the Wayback Machine., World Health Organization, 2013 (hereafter WHO 2013).

- ↑ For "female genital modification," see Gallo, Pia Grassivaro; Tita Eleanora; and Viviani, Franco. "At the Roots of Ethnic Female Genital Modification," in George C. Denniston and Pia Grassivaro Gallo (eds.). Bodily Integrity and the Politics of Circumcision. Springer, 2006, pp. 49–50.

- For the rest, see Momoh, Comfort. Female Genital Mutilation. Radcliffe Publishing, 2005, p. 6.

- ↑ ഉദ്ധരിച്ചതിൽ പിഴവ്: അസാധുവായ

<ref>ടാഗ്;Rahman2000p7എന്ന പേരിലെ അവലംബങ്ങൾക്ക് എഴുത്തൊന്നും നൽകിയിട്ടില്ല. - ↑ ഉദ്ധരിച്ചതിൽ പിഴവ്: അസാധുവായ

<ref>ടാഗ്;toubia1994എന്ന പേരിലെ അവലംബങ്ങൾക്ക് എഴുത്തൊന്നും നൽകിയിട്ടില്ല. - ↑ UNICEF 2013 Archived 2015-04-05 at the Wayback Machine., p. 2

- ↑ UNICEF 2013 Archived 2015-04-05 at the Wayback Machine., pp. 47, 50, 183.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 WHO 2013 Archived 2013-10-25 at the Wayback Machine.; WHO 2008, p. 4

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Abdulcadira, Jasmine; Margairaz, C.; Boulvain, M; Irion, O. "Care of women with female genital mutilation/cutting" Archived 2016-07-18 at the Wayback Machine., Swiss Medical Weekly, 6(14), January 2011 (review).

- ↑ UNICEF 2013 Archived 2015-04-05 at the Wayback Machine., p. 15: "There is a social obligation to conform to the practice and a widespread belief that if they [families] do not, they are likely to pay a price that could include social exclusion, criticism, ridicule, stigma or the inability to find their daughters suitable marriage partners." Nahid F. Toubia, Eiman Hussein Sharief, "Female genital mutilation: have we made progress?" Archived 2017-01-01 at the Wayback Machine., International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 82(3), September 2003, pp. 251–261: "One of the great achievements of the past decade in the field of FGM is the shift in emphasis from the concern over the harmful physical effects it causes to understanding this act as a social phenomenon resulting from a gender definition of women's roles, in particular their sexual and reproductive roles. This shift in emphasis has helped redefine the issues from a clinical disease model (hence the terminology of eradication prevalent in the literature) to a problem resulting from the use of culture to protect social dominance over women's bodies by the patriarchal hierarchy. Understanding the operative mechanisms of patriarchal dominance must also include understanding how women, particularly older married women, are important keepers of that social hegemony." PubMed doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00229-7

- ↑ Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: What Might the Future Hold?, New York: UNICEF, 22 July 2014 (hereafter UNICEF 2014), p. 3/6: "If nothing is done, the number of girls and women affected will grow from 133 million today to 325 million in 2050." Also see p. 6/6:

"Data sources: UNICEF global databases, 2014, based on Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) and other nationally representative surveys, 1997–2013. Population data are from: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2012 revision, CD-ROM edition, United Nations, New York, 2013.

"Notes: Data presented in this brochure cover the 29 countries in Africa and the Middle East where FGM/C is concentrated and for which nationally representative data are available."

- ↑ P. Stanley Yoder, Shane Khan, "Numbers of women circumcised in Africa: The Production of a Total" Archived 2017-11-22 at the Wayback Machine., USAID, DHS Working Papers, No. 39, March 2008, pp. 13–14: "Infibulation is practiced largely in countries located in northeastern Africa: Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan. Survey data are available for Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Djibouti. Sudan alone accounts for about 3.5 million of the women. ... [T]he estimate of the total number of women infibulated in [Djibouti, Somalia, Eritrea, northern Sudan, Ethiopia, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Chad, Nigeria, Cameroon and Tanzania, for women 15–49 years old] comes to 8,245,449, or just over eight million women." Also see Appendix B, Table 2 ("Types of FGC"), p. 19. UNICEF 2013 Archived 2015-04-05 at the Wayback Machine., p. 182, identifies "sewn closed" as most common in Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia for the 15–49 age group (a survey in 2000 in Sudan was not included in the figures), and for the daughters of that age group it is most common in Djibouti, Eritrea, Niger and Somalia. See UNICEF statistical profiles: Djibouti (December 2013), Eritrea (July 2014), Somalia (December 2013). Also see Gerry Mackie, "Ending Footbinding and Infibulation: A Convention Account" Archived 2019-07-20 at the Wayback Machine., American Sociological Review, 61(6), December 1996 (pp. 999–1017), p. 1002: "Infibulation, the harshest practice, occurs contiguously in Egyptian Nubia, the Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia, also known as Islamic Northeast Africa."

- ↑ For countries in which it is outlawed or restricted, UNICEF 2013 Archived 2015-04-05 at the Wayback Machine., p. 8; for enforcement, UNFPA–UNICEF 2012, p. 48.

- ↑ "67/146. Intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilation", United Nations General Assembly, adopted 20 December 2012.

Emma Bonino, "Banning Female Genital Mutilation", The New York Times, 19 December 2012.

- ↑ Eric K. Silverman, "Anthropology and Circumcision", Annual Review of Anthropology, 33, 2004 (pp. 419–445), pp. 420, 427.

- ↑ "Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation", World Health Organization, 2008, pp. 4, 22–28.

- See p. 4, and Annex 2, p. 24, for the classification into Types I, II, III, and IV.

- See Annex 2, pp. 23–28, for a more detailed discussion of the classification.

- See Annex 2, p. 24, for a discussion of Type IV.

- ↑ "Female Genital Mutilation", World Health Organization, February 2013: "1. Clitoridectomy: partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals) and, in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris)."

- Susan Izett and Nahid Toubia write there are no medical reports of Type I being performed without removal of the clitoris. See Izett and Toubia, Female Genital Mutilation: An Overview. World Health Organization, 1998: "Type I. In the commonest form of this procedure the clitoris is held between the thumb and index finger, pulled out and amputated with one stroke of a sharp object. Bleeding is usually stopped by packing the wound with gauzes or other substances and applying a pressure bandage. Modern trained practitioners may insert one or two stitches around the clitoral artery to stop the bleeding."

- Also see "Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation", World Health Organization, 2008, p. 4: "partial or total removal of the clitoris (clitoridectomy) and/or the clitoral hood."

- ↑

"Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation", World Health Organization, 2008, p. 4: "Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (excision)".

- p. 24: "Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (excision). When it is important to distinguish between the major variations that have been documented, the following subdivisions are proposed: Type IIa, removal of the labia minora only; Type IIb, partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora; Type IIc, partial or total removal of the clitoris, the labia minora and the labia majora. Note also that, in French, the term "excision" is often used as a general term covering all types of female genital mutilation."

- ↑ "Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation", World Health Organization, 2008, p. 4: "All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, for example: pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization."

- ↑ Caldwell, John C.; Orubuloye, I.O.; and Caldwell, Pat. "Female Genital Mutilation: Conditions of Decline", Population Research and Policy Review, 19(3), June 2000 (pp. 233–254), p. 235.

- For more information on Djibouti, see Martinelli, M. and Ollé-Goig, J.E. "Female genital mutilation in Djibouti, African Health Sciences, 12(4), December 2012: "In 1997 the Ministry of Health assisted with the United Nation Fund for Population (UNFP) promoted the “Project to Fight Female Circumcision” ... they demonstrated that FGM/C was almost universal among women in Djibouti (98.8 %) and that 68 % of them had been subjected to type III mutilation."

- ↑ "United Nations bans female genital mutilation" Archived 2013-04-21 at the Wayback Machine., UN Women, 20 December 2012.

- ↑ Tamale, Sylvia. "Researching and theorising sexualities," in Sylvia Tamale (ed.). African Sexualities: A Reader. Fahamu/Pambazuka, 2011, pp. 19–20.

കൂടുതൽ വായനയ്ക്ക്

[തിരുത്തുക]- റിസോഴ്സുകൾ

- Campaign Against Female Genital Mutilation, International Campaign Against FGM.

- End FGM campaign Archived 2013-05-17 at the Wayback Machine., End FGM European campaign run by Amnesty International.

- FORWARD, The Foundation for Women's Health, Research and Development.

- "Hospitals and Clinics in the UK offering Specialist FGM (Female Genital Mutilation) Services" Archived 2014-03-28 at the Wayback Machine., FORWARD.

- ഗ്രന്ഥങ്ങൾ

- Abdalla, Raqiya Haji Dualeh. Sisters in Affliction: Circumcision and Infibulation of Women in Africa. Zed Books, 1982.

- Aldeeb, Sami. Male & Female circumcision: Among Jews, Christians and Muslims. Shangri-La Publications, 2001.

- Dettwyler, Katherine A. Dancing Skeletons: Life and Death in West Africa. Waveland Press, 1994.

- Dorkenoo, Efua. Cutting the Rose: Female Genital Mutilation. Minority Rights Publications, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, 1996.

- Mernissi, Fatima. Beyond the Veil: Male-Female Dynamics in a Modern Muslim Society. Indiana University Press, 1987 [first published 1975].

- Sanderson, Lilian Passmore. Against the Mutilation of Women. Ithaca Press, 1981.

- Skaine, Rosemarie. Female Genital Mutilation. McFarland & Company, 2005.

- Walker, Alice. Possessing the Secret of Joy. New Press, 1993 (novel).

- Zabus, Chantal. Between Rites and Rights: Excision on Trial in African Women's Texts and Human Contexts. Stanford University Press, 2007.

- വ്യക്തികളുടെ അനുഭവങ്ങൾ

- Ali, Ayaan Hirsi. Infidel: My Life. Simon & Schuster, 2007: Ali experiences FGM at the hands of her grandmother.

- Dirie, Waris. Desert Flower. Harper Perennial, 1999: autobiographical novel about Dirie's childhood and genital mutilation.

- Dirie, Waris. Desert Dawn. Little, Brown, 2003: how Dirie became a UN Special Ambassador for FGM.

- Dirie, Waris. Desert Children. Virago, 2007: FGM in Europe.

- El Saadawi, Nawal. Woman at Point Zero. Zed Books, 1975.

- Williams-Garcia, Rita. No Laughter Here. HarperCollins, 2004: a ten-year-old Nigerian girl undergoes FGM while on vacation in her homeland.

- ലേഖനങ്ങൾ

- Abusharaf, Rogaia Mustafa. "Virtuous Cuts: Female Genital Circumcision in an African Ontology" Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine., Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, vol 12, 2001, pp. 112–140.

- Althaus, Francis A. "Female Circumcision: Rite of Passage Or Violation of Rights?", International Family Planning Perspectives, 23(3), September 1997.

- Boddy, Janice. "Womb as oasis: The symbolic context of Pharaonic circumcision in rural Northerm Sudan", American Ethnologist, 9(4), November 1982.

- Chase, Cheryl. "'Cultural practice' or 'Reconstructive Surgery'? U.S. Genital Cutting, the Intersex Movement, and Medical Double Standards", in Stanlie M. James and Claire C. Robertson (eds.). Genital Cutting and Transnational Sisterhood. University of Illinois Press, 2002.

- Darugar, Maliha A; Harris, Rebecca M; and Frader, Joel E. "Consent and cultural conflicts: ethical issues in pediatric anesthesiologists' participation in female genital cutting", in Gail A. Van Norman et al. Clinical Ethics in Anesthesiology: A Case-Based Textbook. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Ehrenreich, Nancy and Barr, Mark. "Intersex Surgery, Female Genital Cutting, and the Selective Condemnation of 'Cultural Practices'", Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 40(1), 2005, pp. 71–140.

- Ferguson, Ian and Ellis, Pamela. "Female Genital Mutilation: a Review of the Current Literature", Research Section, Department of Justice, Canada, 1995.

- Haworth, Abigail. "The day I saw 248 girls suffering genital mutilation", The Guardian, 18 November 2012.

- Kouba, Leonard and Muascher, Judith. "Female Circumcision in Africa: An Overview", African Studies Review, 28(1), March 1985, pp. 95–110.

- Oguntoye, Susana. "'FGM is with us Everyday': Women and Girls Speak Out about Female Genital Mutilation in the UK" Archived 2013-06-25 at the Wayback Machine., World Academy of Science and Engineering, vol 54, 2009.

- Population Reference Bureau. "Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Data and Trends" Archived 2012-09-28 at the Wayback Machine., 2008.

- Shell-Duncan, Bettina. "The medicalization of female "circumcision": harm reduction or promotion of a dangerous practice? Archived 2012-11-02 at the Wayback Machine., Social Science & Medicine, 52(7), 2001, pp. 1013–1028.

- UNICEF. "Coordinated Strategy to Abandon Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in One Generation".

- Westley, David M. "Female circumcision and infibulation in Africa" Archived 2021-06-05 at the Wayback Machine., Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography, 4, 1999 (contains an extensive bibliography).

- ചലച്ചിത്രങ്ങൾ

- Brendecke, Dagmar and Müller-Belecke, Anke. Schnitt ins Leben – Afrikanerinnen bekämpfen ein Ritual. Germany, 2000 (documentary).

- Dacosse, Marc and Eric Dagostino, Eric. L’Appel de Diégoune (Walking the Path of Unity). Tostan, France, 2009; link courtesy of Tostan International, YouTube.

- Eran, Doron. God's Sandbox. Israel, 2006: An Israeli girl joins a Muslim tribe and is forced to undergo FGM.

- Hormann, Sherry. Desert Flower. 2009: Based on Waris Dirie's book, Desert Flower.

- Johnson, Kirsten and Pimsleur, Julia. Bintou in Paris. France, 1995 (documentary).

- Kouros, Alex. Kokonainen. Finland, 2005: won the 2005 New York Short Film Festival Jury Award for Best Screenplay.

- Longinotto, Kim. The Day I Will Never Forget. UK, 2002.

- Maldonado, Fabiola. Maimouna – La vie devant moi. Germany, 2007 (documentary).

- Pomerance, Erica. Dabla! Excision. Canada, 2003: Follows the growing movement across Africa to stop FGM.

- Sembène, Ousmane. Moolaadé. Senegal, France, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Morocco, Tunisia, 2004.

- Sissoko, Cheick Oumar. Finzan. Mali, 1989: Two women rebel against the traditions of a village society.

- Wilkins, Oliver. Short film on FGM in Minya, Egypt Archived 2013-05-14 at the Wayback Machine., vimeo.com.