സോബിബോർ എക്സ്റ്റർമിനേഷൻ ക്യാമ്പ്

| Sobibór | |

|---|---|

| Extermination camp | |

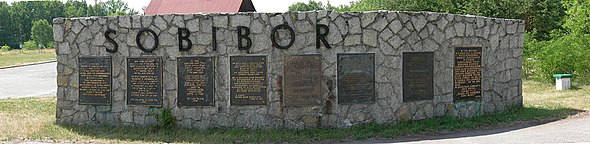

Sobibór extermination camp memorial, pyramid of sand mixed with human ashes  Location of Sobibór (right of centre) on the map of German extermination camps marked with black and white skulls. Poland's borders before the Second World War | |

| Coordinates | 51°26′50″N 23°35′37″E / 51.44722°N 23.59361°E |

| Other names | SS-Sonderkommando Sobibor |

| Known for | Genocide during the Holocaust |

| Location | Near Sobibór, General Government (occupied Poland) |

| Built by |

|

| Original use | Extermination camp |

| First built | March 1942 – May 1942 |

| Operational | 16 May 1942 – 14 October 1943 |

| Number of gas chambers | 3 (expanded to 6)[1] |

| Inmates | Jews mainly from Poland, but also from France, Germany, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union (including POWs) |

| Number of inmates | Est. 600–650 slave labour at any given time |

| Killed | Est. min. 200,000–250,000 |

| Notable inmates | Joseph Serchuk, Dov Freiberg, Alexander Pechersky |

രണ്ടാം ലോകമഹായുദ്ധ കാലഘട്ടത്തിൽ നിയന്ത്രിത സെക്കന്റ് പോളീഷ് റിപ്പബ്ലിക്കിലെ ജനറൽ ഗവൺമെന്റിന്റെ സെമി കൊളോണിയൽ പൊതു ഭരണകൂടത്തിനകത്ത്, സോബിബൂർ റെയിൽവേ സ്റ്റേഷന് സമീപം എസ്.എസ് നിർമ്മിച്ചതും നടത്തിയിരുന്നതുമായ ഒരു നാസി ജർമ്മൻ ഉന്മൂലന ക്യാമ്പായായിരുന്നു സോബിബോർ എക്സ്റ്റർമിനേഷൻ ക്യാമ്പ് (അല്ലെങ്കിൽ സോബീബോർ / sɔːbibɔːr /പോളിഷ്: [sɔbʲibur]) (Sobibór extermination camp) [2] / soʊbiː - /; [3]ജർമ്മൻ അധിനിവേശ പോളണ്ടിലെ ഹോളോകാസ്റ്റിന്റെ ഏറ്റവും നിർണായക ഘടകം, രഹസ്യ ഓപ്പറേഷൻ റെയ്ൻഹാർഡ് എന്നതിന്റെ ഭാഗമായിരുന്നു ക്യാമ്പ്. പ്രവിശ്യ തലസ്ഥാനമായ ബ്രസ്റ്റ്-ഓൺ-ദി-ബഗ് (പോളീഷിൽ ബ്രസെസ്ക് നഡ് ബുഗീം) യിൽ നിന്ന് 85 കിലോമീറ്റർ തെക്ക് ഗ്രാമത്തിനടുത്തുള്ള വലോദാവയ്ക്ക് (ജർമ്മൻകാർ വെൽസെയ്ക്ക് എന്നും വിളിച്ചിരുന്നു) ഈ ക്യാമ്പ് സ്ഥിതിചെയ്യുന്നു. ഇതിന്റെ ഔദ്യോഗിക ജർമ്മൻ പേര് എസ്.എസ്. സോണ്ടർകോമണ്ടൊ സോബീബൊർ ആയിരുന്നു.[4]

ആജ്ഞയുടെ ശൃംഖല[തിരുത്തുക]

Name Rank Function and Notes Citation Organisers of the camp (Germans and one former Austrian) Odilo Globocnik SS-Brigadeführer Major-General and SS Police Chief (SS-Polizeiführer) at the time, Head of Operation Reinhard [1] Hermann Höfle SS-Hauptsturmführer Captain, Coordinator of Operation Reinhard Richard Thomalla SS-Obersturmführer First Lieutenant, Head of death camp construction during Operation Reinhard [1] Erwin Lambert SS-Unterscharführer Corporal, Head of gas chamber construction during Operation Reinhard Karl Steubl SS-Sturmbannführer Major, Commander of transportation units during Operation Reinhard [5] Christian Wirth SS-Hauptsturmführer Captain at the time, Inspector of Operation Reinhard Commandants (Germans and Austrians) Franz Stangl SS-Obersturmführer First Lieutenant, Error in Template:Date table sorting: 'April' is not a valid month – Error in Template:Date table sorting: 'August' is not a valid month transferred to Commandant of Treblinka extermination camp [1] [5] Franz Reichleitner SS-Obersturmführer First Lieutenant, Error in Template:Date table sorting: 'September' is not a valid month – Error in Template:Date table sorting: 'October' is not a valid month;[1] promoted to Captain (Hauptsturmführer) after Himmler's visit on Error in Template:Date table sorting: 'February' is not a valid month [5] Deputy commandants (Germans and Austrians) Gustav Wagner SS-Oberscharführer Staff Sergeant, Deputy commandant (Quartermaster, sergeant major of the camp) [1] ;[5] Johann Niemann SS-Untersturmführer Second Lieutenant, Deputy commandant, killed in the revolt [5] Karl Frenzel SS-Oberscharführer Staff Sergeant, Commandant of Camp I (forced labor camp) [1] [5] Hermann Michel SS-Oberscharführer Staff Sergeant, Deputy commandant, gave speeches to trick condemned prisoners into entering gas chambers [5] [6] Gas chamber executioners (Germans ) Erich Bauer SS-Oberscharführer Staff Sergeant, operated gas chambers [1] ;[5] Kurt Bolender SS-Oberscharführer Staff Sergeant, gas chambers' operator [1] [5] Other staff officers (Germans and Austrians) Ernst Bauch committed suicide in December 1942 on vacation in Berlin from his Sobibor duty [5] Rudolf Beckmann SS-Oberscharführer Staff Sergeant, killed in revolt [5] Gerhardt Börner SS-Untersturmführer Second Lieutenant [7] Paul Bredow SS-Unterscharführer Corporal, managed the "Lazarett" killing station [1] [5] Max Bree killed in the revolt [5] Arthur Dachsel police sergeant, transferred from Belzec in 1942, burning of corpses (Sonnenstein) [5] Werner Karl Dubois SS-Oberscharführer Staff Sergeant [1] [5] Herbert Floss SS-Scharführer Sergeant [1] [5] Erich Fuchs SS-Scharführer Sergeant [1] [5] [7] Friedrich Gaulstich SS-Scharführer Sergeant, killed in the revolt [5] Anton Getzinger [5] Hubert Gomerski SS-Unterscharführer Corporal [5] Siegfried Graetschus SS-Oberscharführer Staff Sergeant, Head of Ukrainian Guard (2/2), killed in the revolt [1] ;[5] Ferdinand "Ferdl" Grömer Austrian cook, helped also with gassings [5] Paul Johannes Groth supervised sorting of clothes in Lager II Lorenz Hackenholt SS-Hauptscharführer First Sergeant Josef Hirtreiter SS-Scharführer Sergeant, transferred from Treblinka in October 1943 for a short while [1] Franz Hödl [5] Jakob Alfred Ittner SS-Oberscharführer Staff Sergeant [5] Robert Jührs SS-Unterscharführer Corporal Aleks Kaizer Rudolf "Rudi" Kamm [5] Johann Klier SS-Untersturmführer Second Lieutenant [5] Fritz Konrad SS-Scharführer Sergeant, killed in the revolt [5] Erich Lachmann SS-Scharführer Sergeant, Head of Ukrainian Guard (1/2) [5] Karl Emil Ludwig [5] Willi Mentz SS-Unterscharführer Corporal, transferred from Treblinka for a short time in December 1943 Adolf Müller [5] Walter Anton Nowak SS-Scharführer Sergeant, killed in the revolt [1] [5] Wenzel Fritz Rehwald [5] Karl Richter [5] Paul Rost SS-Untersturmführer Second Lieutenant [1] Walter "Ryba" (real name: Hochberg) SS-Unterscharführer Corporal, killed in the revolt [5] Klaus Schreiber Hans-Heinz Friedrich Karl Schütt SS-Scharführer Sergeant [1] [5] Thomas Steffl SS-Scharführer Sergeant, killed in the revolt [5] < Ernst Stengelin killed in revolt [5] Heinrich Unverhau SS-Unterscharführer Corporal [5] Josef Vallaster SS-Scharführer Sergeant, killed in the revolt [5] Otto Weiss commandant of the Bahnhof-kommando at Lager I before Frenzel [5] Wilhelm "Willie" Wendland [5] Franz Wolf SS-Oberscharführer Staff Sergeant, brother of Josef Wolf (below) [1] [5] Josef Wolf SS-Scharführer Sergeant, killed in the revolt [5] Ernst Zierke SS-Unterscharführer Corporal Heinrich Barbl SS-Rottenführer Private First Class, pipes for the gas chambers (from Action T4) [5][8] Wachmänner guards (Ukrainians and Russians)

Sobibór "Road to Heaven" in 2007 - Volksdeutsche and up to 200 Trawniki men (former Soviet prisoners-of-war of various ethnicities trained at the SS compound in Trawniki)

- Ivan Klatt[9]

- Emanuel Schultz

- Russian

- B. Bielakow

- Ivan Nikiforow

- Mikhail Affanaseivitch Razgonayev[10]

- J. Zajcew

- Ukrainian

- Ivan Demjanjuk[11] (alleged; conviction pending appeal not upheld by German criminal court)

- Emil Kostenko

- M. Matwiejenko

- W. Podienko

- Fiodor Tichonowski

| Timeline of Sobibór, March 1942 – October 1943 | |

|---|---|

| March 1942 | Under the supervision of Richard Thomalla, SS and police authorities construct Sobibór extermination camp in the spring of 1942 in an isolated area not far from the local Chelm-Wlodawa rail line. |

| April 1942 | The first test subjects for the gas chambers at Sobibór: The SS deports 2,400 Jews from Rejowiec, Lublin Voivodeship in early April 1942, the first deportation to Sobibór, and murders almost all of them upon arrival. |

| 28 April 1942 | Franz Stangl arrives in Sobibór to take up the position of camp commandant. Stangl had been the deputy supervisor of the "euthanasia" institution at Hartheim, near Linz, Austria. As the purpose of the "euthanasia" operation was to murder institutionalised persons with physical and mental disabilities in gas chambers at facilities like Hartheim, Stangl was familiar with using carbon monoxide gas for killing large numbers of people. |

| 3 May 1942 | Regular transports to Sobibór begin. The first transport consists of 200 Jews from Zamość. The camp staff conducts gassing operations in three gas chambers located in one brick building. Some 400 prisoners are selected to survive, temporarily, to supply manual labour necessary to support the mass murder function of the killing centre. During this first phase of deportations, from early May until the end of July 1942, the Sobibór killing centre authorities kill at least 61,400 Jews. Many of them were deported from cities and towns in the north and east of Lublin District; the majority were Jews deported from the German Reich, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and Slovakia either directly or via the transit camp-ghetto in Izbica. |

| July/August 1942 | The SS halts deportations to Sobibór in order to modernise the railway spur into the camp. |

| 8 October 1942 | Camp authorities resume mass murder operations in the gas chambers of Sobibór with the arrival of more than 24,000 Slovak Jews between 8 and 20 October from the transit camp-ghetto Izbica in the Lublin District of the General Government. The camp authorities kill virtually all of the deportees upon arrival in reconstructed and newly added gas chambers, completed during the two-month lull in transports to Sobibór. The improvements in capacity enable the camp authorities to kill up to 1,300 people at a time. Newly constructed as well was a narrow railway trolley from the reception platform to the burial pits in order to facilitate the transfer of the sick, the dead and those unable to walk directly to the open ovens. Those still alive after this journey are shot by the SS staff or the Trawniki-trained guards. |

| 12 February 1943 | Heinrich Himmler visits Sobibór to inspect operations. Several SS officers at the camp are promoted as a result. |

| 5 March 1943 | Deportations from the Netherlands. German SS and Police authorities begin deportations of Dutch Jews from transit camp Westerbork to Sobibór. In 19 transports from this date until July 1943, SS authorities in Westerbork deport over 34,000 Jews to Sobibór. Camp staff and guards kill almost all of them in the gas chambers or by shooting on arrival in the camp. |

| April 1943 | Deportations from France. Two transports containing a total of 2,000 Jews from France arrive at Sobibór from the police transit camp Drancy, outside Paris. Deportations from France to camps in the east, primarily Auschwitz, began in March 1942 and continue until August 1944. |

| July/October 1943 | Deportations from the Soviet Union. Following Himmler's order of July 1943 to liquidate the ghettos in Reichskommissariat Ostland, SS and police units liquidate ghettos in Minsk, Lida and Wilno (Vilnius, Vilne) and deport those who survived to Sobibór. The first transports from Minsk and Lida leave for Sobibór on 18 September. Included in the first deportation from Minsk (arrived 22 September) is Alexander "Sasha" Pechersky, a Soviet-Jewish prisoner of war, who, because of his military training, came to play a central role in the resistance movement in Sobibór. In September 1943 alone, SS and police authorities transported at least 13,700 Jews from ghettos in the occupied Soviet Union to Sobibór. The camp authorities gas or shoot most of them upon arrival. |

| 14 October 1943 | Sobibór revolt. Prisoners carry out a revolt in Sobibór, killing close to a dozen German staff and Trawniki-trained guards. Of 600 prisoners left in Sobibór on this day, roughly 300 escape during the uprising.[1] Among the survivors is Alexander Pechersky, the Soviet prisoner-of-war who played a key role in planning the revolt. Of those who escape, the SS and police personnel from Lublin district recapture and shoot some 140. Some of the prisoners selected for temporary survival in Sobibór organised an underground resistance organisation in early summer of 1943 as it became apparent that gassing operations at Sobibór were slowing. Once the gassing operations were finished, the SS planned to dismantle the killing centre and reconfigure the facility first as a holding pen for women and children deported from villages in Belarus, which had been destroyed in the course of so-called anti-partisan operations, and, later, as an ammunition depot. Though no further prisoners arrived after the killing centre was remodelled, the facility was guarded by a small Trawniki-trained detachment until at least the end of March 1944. During the year and a half in which the Sobibór killing centre operated, camp authorities and the Trawniki-trained guards murdered at least 167,000 people. Virtually all of the victims were Jews. |

| 17 October 1943 | Heinrich Himmler orders that Sobibór be closed and all evidence of the camp's existence be removed.[1] |

-

Memorial at Sobibór Museum entrance

-

Sobibór railway yard

-

Memorial inside the camp

ഇതും കാണുക[തിരുത്തുക]

Notes[തിരുത്തുക]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 Lest we forget (14 March 2004), ""Extermination camp Sobibor"". Archived from the original on 7 മാർച്ച് 2005. Retrieved 7 മാർച്ച് 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) The Holocaust. Retrieved on 17 May 2013. - ↑ Howjsay.com

- ↑ CMU Pronouncing Dictionary

- ↑ William L. Shirer (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany (3 ed., 1960). Simon and Schuster. p. 968. ISBN 0671728687. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 5.26 5.27 5.28 5.29 5.30 5.31 5.32 5.33 5.34 5.35 5.36 5.37 5.38 5.39 5.40 5.41 5.42 5.43 Jules Schelvis & Dunya Breur. "Biographies of SS-men – Sobibor Interviews". Sobiborinterviews.nl. NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

The core of this website consists of thirteen interviews with survivors of the uprising on 14 October 1943 in the Sobibor extermination camp, originally recorded in 1983 and 1984 forty years after the fact.

- ↑ Nizkor Web Site Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 9 April 2009

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Klee, Ernst, Dressen, Willi, Riess, Volker The Good Old Days: The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders. ISBN 1-56852-133-2.

- ↑ Robin O'Neil (2009). "6". Belzec: Stepping Stone to Genocide. JewishGen.org. ISBN 0976475936.

- ↑ "Survivors of the revolt – Sobibor Interviews". sobiborinterviews.nl.

- ↑ "Interrogation of Mikhail Affanaseivitch Razgonayev Sobibor Death Camp Wachman - www.HolocaustResearchProject.org". holocaustresearchproject.org.

- ↑ BBC News (12 May 2011). "John Demjanjuk guilty of Nazi death camp murders". Retrieved 12 May 2011.

References[തിരുത്തുക]

- Obóz zagłady w Sobiborze [Death camp in Sobibor] (in പോളിഷ്), Warsaw: Virtual Shtetl, Museum of the History of Polish Jews, 2010, 1 of 3, retrieved 16 June 2016

{{citation}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - Jakub Chmielewski (2014), Obóz zagłady w Sobiborze [Death camp in Sobibor] (in പോളിഷ്), Lublin: Ośrodek Brama Grodzka, Pamięć Miejsca, archived from the original on 2014-10-12, retrieved 25 September 2014

{{citation}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Sobibor Museum (2014) [2006], Historia obozu [Camp history], Dr. Krzysztof Skwirowski, Majdanek State Museum, Branch in Sobibór (Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku, Oddział: Muzeum Byłego Obozu Zagłady w Sobiborze), archived from the original on 2013-05-07, retrieved 25 September 2014

- Arad, Yitzhak (1987). Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253213053. Amazon Kindle, also in: Google Books, Snippet view, digitized from U. of Michigan, 2008.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bialowitz, Philip; Bialowitz, Joseph (2010). A Promise at Sobibor: A Jewish Boy's Story of Revolt and Survival in Nazi Occupied Poland. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-24800-0. With Foreword by Władysław Bartoszewski.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blatt, Thomas (1997). From the Ashes of Sobibor. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0810113023 – via Google Books preview.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Freiberg, Dov (2007), To Survive Sobibor, Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 978-965-229-388-6

- Lev, Michael (2007), Sobibor, Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 978-965-229-408-1

- Novitch, Miriam (1980). Sobibor, Martyrdom and Revolt: Documents and Testimonies. ISBN 0-89604-016-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schelvis, Jules (2014) [2007]. Sobibor: A History of a Nazi Death Camp. Translated by Dixon, Karin. Berg Publishers (2007), Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014. ISBN 1472589068 – via Google Books, preview.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sereny, Gitta (1974). Into That Darkness: from Mercy Killing to Mass Murder. ISBN 0-07-056290-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gilead, Isaac; Haimi, Yoram; Mazurek, Wojciech (2009), Excavating Nazi Extermination Centres. Archived 2018-06-02 at the Wayback Machine. Present Pasts, Vol 1. Published by Ubiquity Press, ISSN 1759-2941

- Zielinski, Andrew (2003), "Conversations with Regina", Zedartz Archived 2013-09-14 at the Wayback Machine. – Hyde Park Press Adelaide Archived 2017-02-04 at the Wayback Machine.. ISBN 0-9750766-0-4

External links[തിരുത്തുക]

- Sobibor on the Yad Vashem website

- SOBIBOR at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- The Sobibor Death Camp at HolocaustResearchProject.org

- Sobibor Archaeological Project at Israel Hayom

- Archaeological Excavations at Sobibór Extermination Site Archived 2019-05-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- Survivor Thomas Blatt, 18-minute audio interview by WMRA

- International archeological research in the area of the former German-Nazi extermination camp in Sobibór.

- Onderzoek – Vernietigingskamp Sobibor (records of testimonies, transportation lists and other documents, from the archives of the NIOD Instituut voor Oorlogs-, Holocaust- en Genocidestudies, Netherlands)

- Archaeological Excavations at Sobibór Extermination Site Archived 2017-12-03 at the Wayback Machine., at Yad Vashem website